Re-examining Patriarchy and Faith: Domestic Violence and Faith Integration in Nigeria By Michael Olatunbosun.

The book, Domestic Violence and Faith Integration in Nigeria written by Dr Adebola Ishola, (2023, Jedidiah Prints) focuses on the menace of domestic violence, its enablers and how all critical stakeholders can contribute to its mitigation. The author is a political scientist and seasoned administrator, with years of experience researching about her thematic focus in the book. She is therefore fit to write about the menace of domestic violence in the African society.

In the book, Dr Ishola defines domestic violence as an “act of causing physical, psychological, emotional, sexual, and economic harm or injury to its victim in different ways” (p1) and submits that it is pervasive across all countries, social classes, families and religions. Quoting the United Nations, the author writes that 70% of women experience some forms of gender-based violence in their lifetime.

She writes that in Nigeria, there has been an upsurge of domestic violence, and she makes reference to some reported cases of abuse.

In this book, the author argues that anybody can be a victim of domestic violence as it knows no gender, race, religion or social class. It is essentially a pattern of abusive behaviour from the abuser to the abused where the abuser exerts control and power over the abused person.

From the foregoing therefore, the thinking that only women are abused or battered by the male folks is incorrect. The author states (p12) that “one in three women has experienced some form of violence from a partner compared to one in four men. … One out of two women who are murdered is killed by their intimate partners, as against one in thirteen men killed by their partners.” Then the author deploys data to back up her point.

For instance, the author, quoting newspaper reports, states that as of 16th September of 2017, 852 cases of domestic violence were recorded between January and September of the same year in Lagos State alone. She also writes that while many religious communities provide support services for survivors of domestic violence, some of the abused are forced to remain with their partners based on religious doctrines preached to the adherents of the given religion.

The author laments the adverse impact of society’s patriarchal tendencies and avers (p13) that “attack and severe assault by husbands on non-violent wives outnumber severe assault by wives of non-violent husbands by three to one.” By this submission, the author believes that violence by wives is often defensive rather than offensive. Then the author highlights the types and forms of domestic abuse to include repeated physical or sexual assault, physical violence, sexual jealousy, sexual abuse or violence, deprivation, neglect, psychological torture and so on.

In this book, the author enumerates the warning signals of abuse in a relationship, she discusses domestic violence as it is meted out to children, and reports that it includes all forms of violence against people under age 18 either by parents of the child, caregivers, peers or strangers. Quoting statistics, she reports that one in 15 children is exposed to intimate partner violence each year and 90% of them are eye witnesses to this violence. Indeed, she notes that female circumcision commonly known as female genital mutilation, early marriage and many others are forms of violence against children. In the section on domestic violence against children (chapter three), the author prescribes what to do to help children recover from domestic violence (Pp48-50). Then Dr Adebola follows this up with a mention of the effects of domestic violence on children.

In the book, the author dedicates time to exposing the many shades of domestic violence and its causes, and also discusses parental responsibilities and the negative impact of abdication of these responsibilities by parents.

In the book, the author also discusses an often less discussed issue of violence against the elderly, orphans and persons with disabilities. For her, violence against these vulnerable groups is often perpetrated by their children, by people looking after them, or some other family members. Even workers of nursing homes and care facilities for the elderly sometimes mete out violence on the elderly. And abuse against the elderly can be psychological, physical and financial in nature. In fact, many elderly people are abandoned in their homes and left at the mercy of house keepers who might not have the requisite training and compassion for taking care of the elderly.

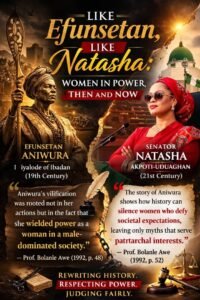

In the book, Domestic Violence and Faith Integration in Nigeria, Dr Adebola dedicates the whole of chapter five to discussing some factors that enable domestic violence, especially in Africa. Her first anger is against the deep patriarchal influence which encourages male dominance. For the author, the culture that makes the man to feel that he has the right to treat the woman the way he desires is permissive to violence. This idea is derived from the sense of ownership conferred on the man by the payment of bride price. So, a man is assumed to have “purchased” his wife, and he automatically takes full ownership of the woman.

Among other things therefore, the author identifies age disparity between couples, upbringing and personal disorders, family background and the effect of alcohol and hard drugs as some of the causes of domestic violence.

Indeed, the impact of religion or faith on domestic violence is a key theme in this book. The author quotes copiously (chapter eight) from the Christian scriptures to indicate divine teachings about courtship, marriage, divorce, separation and domestic violence. She avers that God created man and woman for each other, for companionship, procreation and mutual happiness, but laments that many homes of today reflect the opposite of this divine creation. According to the author, it is unfortunate tha many people hide under the scriptural submission mandate (p123) of the wife to abuse their wives. She argues here that many misconstrue the idea that God hates divorce to mean that they can continue to suppress and subjugate the woman. In the opinion of the author, men must respect the scriptural order that men should love their wives and honour them, too. “A man who wants the wife to submit to him must show his unconditional love to the wife,” she argues (p124).

She also highlights the contribution of society to domestic violence as well as the whole gamut of legal environment on violence and abuse.

In the final analysis this 12-chapter book is a powerful resource on domestic and gender based violence, and essentially breaks down the problem, providing solutions and recommendations for mitigating violence in Nigeria.

Olatunbosun is a broadcast journalist, fact checker and book reviewer at Spash FM 105.5, Ibadan. He can be reached via molatunbosun@splashfm1055.com, on X and Instagram @miketunbosun.